Now and then, the media publish information about the poor, inefficient, badly functioning Czech system of education and about Czech pupils’ weak, poor or even deficient knowledge. Understandably, different groups of people may see things in a different light. Thus experience with the so-called quality of the Czech education system may also vary among teachers, parents and those who “it is all about”– children.

… children do not like going to school as they feel bored, do not want to study, or do not feel like it.

Last year I studied the results of the international research studies TIMSS and PISA, which tried to find out, among other, things, fifteen-year-old pupils' interest in learning. What was the result? Unequivocal – children do not like going to school as they feel bored, do not want to learn, do not feel like it. I believe that anyone who cares about the students who leave Czech schools, who wants the graduates to be creative, thoughtful, self-confident and socially skilled, (which is essential if they are to become valid members of our society,) cannot be indifferent to the unfavourable results of the international studies. The results made me ask a number of questions.

… if pupils are to acquire good knowledge, it is essential that there should be good relationships and trust in the school.

It is crucially important for me to find out why the situation is such and what to do about it. I have been a teacher of mathematics at the elementary school Základní škola Dr. J. Malíka in Chrudim since 1992. I was lucky enough that immediately after graduation from the Faculty of Education I started to work at a school whose headmaster was at that time (and still is) Zdeněk Brož, a person who has always been aware of the fact that if pupils are to acquire good knowledge, it is essential there should be good relationships and trust in the school. All teachers of the school identify with this point of view. We have always tried to make our pupils regard school as an environment that is interesting, stimulating, where they can learn something new.

Soon I came to the sad conclusion that many children have very little or no interest in mathematics.

I started work in this newly established school as an enthusiastic novice – with great expectations. Children from different schools became classmates and new peer groups were formed. Soon I came to the sad conclusion that many children had very little or no interest in mathematics. When I told the children that “I like mathematics”, they replied, in the best case, that they were good at maths but could not solve word problems. Quite often, I was sorry to hear and see that subjects like mathematics or Czech are absolutely uninteresting for them. It made me ask “Why?”.

Most often, they spoke of their fear they would make a mistake, that someone would laugh at them. They said they did not manage to say anything because there would always be someone faster etc.

It was not difficult to find the answer. Their experience with mathematics lessons affected their attitude to mathematics negatively. Most often, they spoke of their fear they would make a mistake, that someone would laugh at them. They said they did not manage to say anything because there would always be someone faster etc. My goal was to dispel these worries and to work with the children in a way to make them feel safe, to deconstruct the “walls” built around them, to give them the opportunity to let their natural mathematical inquisitiveness show. I hoped this would make them “like mathematics” and thus support their longing to learn more. I have always tried hard to make my lessons meaningful, to allow my pupils to see what and why we were learning.

I was very pleased and encouraged by the fact that the “walls” started cracking and collapsing soon.

I was very pleased and encouraged by the fact that the “walls” started cracking and collapsing soon. I got positive feedback not only from my pupils but also from their parents. I think it is natural to feel the need to improve one’s work. That is why I kept reflecting on what I could do in a different and better way to ensure my work would suit all the children and all of them would find it to be “their cup of tea”.

At that moment, I could hear words like “Hurray, I have the solution” and “Hush, don’t tell us, we want to solve it ourselves” more often.

An important moment in my career was meeting professor Milan Hejný. I started to learn more about the way of teaching of mathematics that he had been developing with his father, Vít Hejný. After a few meetings with him I rejoiced – yes, that’s it! Together with my 6th graders I started piloting teaching materials for the Hejný method at lower secondary school level. At that moment, I could hear words like “Hurray, I have the solution” and “Hush, don’t tell us, we want to solve it ourselves” more often. Suddenly a number of wonderful stories worth publishing were developing before my very eyes.

Let me share Lenka’s story with you.

Let me share Lenka’s story with you. 8th graders had worked out solutions for a given mathematics problem and we were informing each other about the strategies they had used. I was excited when Lenka was the first person to start explaining her way of solving it. She is a girl for whom it is difficult to look for and find connections, she does not see them immediately. This makes her a very interesting person to study for her development in mathematics:

She turned attention to her appearance, a mirror and a comb would rarely not be on her desk

In the sixth grade, Lenka was whimsical. Ii is true she tended to join in the work quite a lot and enjoyed it whenever she was successful, especially if it meant no extra effort – that was not needed yet. She was able to solve basic mathematics problems and would most often get a C in mathematics. In the seventh grade, I could observe a decline in her performance. She turned attention to her appearance, a mirror and a comb would rarely be absent on her desk (I can understand even that at her age). In addition, problems in the family started and Lenka’s resignation from what was going on in lessons was marked. Lenka’s school results went down. Whenever she was offered help, she did not refuse it but I could see she did not identify with the offer internally. In the first term of the school year, her result in mathematics was a D.

“I realized that what we did was important and I had to concentrate – and what is more, I want to.”

I consulted the case with my colleagues, who agreed that Lenka’s situation and reactions in their subjects were similar. We kept asking what we could do about it. I noticed that Lenka was getting closer to Viky. Viky is a girl whom I call “the driving force” in our work secretly. The girls were happy with my proposal that they would sit together. The situation started to improve quite fast. Viky kept encouraging her classmate to work (“you can do that, try it again, see”). She did it intensively, with unceasing energy so typical for her. And it started to work. It was interesting and gratifying to see Lenka “catching on” again. When talking to the children during our on-going reflection and feedback session Lenka said the following: “I realized that what we did was important and I had to concentrate – and what is more, I want to.”

Together with her classmates we worked on Lenka’s self-confidence.

At the end of the school year, her evaluation in mathematics was a C again. In the 8th grade, she became absolutely focused, she kept asking about things she did not understand, she wanted to know. However, she did not feel like sharing her opinions with the others yet. I felt she was too shy to do that. We talked with each other why it was so and she told me it took her longer to understand things and before she grasped the problem someone else would answer. That is why together with her classmates we worked on Lenka’s self-confidence. It is Viky who is most responsible for the positive change in Lenka’s work commitment. When I could hear the loud whisper “Lenka, Lenka, go and show it, it’s really good!” and saw Lenka, first with hesitation, rising from her chair, “my heart pounded” (although you will think I am exaggerating).

“Some people are born with the ability to solve problems and tasks quickly or to understand physics easily, my strong points are languages.”

Lenka is now in the 9th grade and I dare say she is on the right track. She works consistently, she is focused and reliable. She now understands her strengths and weaknesses and knows how to work with them. It can be seen in her self-assessment: “Some people are born with the ability to solve problems and tasks quickly or to understand physics easily, my strong points are languages. Mathematics will never be a piece of cake for me. But I can now praise myself for the great effort in almost all activities that we do. And naturally I must praise you, since you are my motivation to becoming better. Thank you for that!”

Success stimulates them to solve more problems that are chosen in a way to represent an adequate challenge for the children.

I hope the above story illustrates well enough that teaching mathematics using the Hejný method focuses not only on the content but at the same time it develops creative and stimulating environment. It allows children to experience the pleasure of getting the right solution. Success stimulates them to solve more problems that are chosen in a way to represent an adequate challenge for the children. They often regard it as solving a puzzle or riddle.

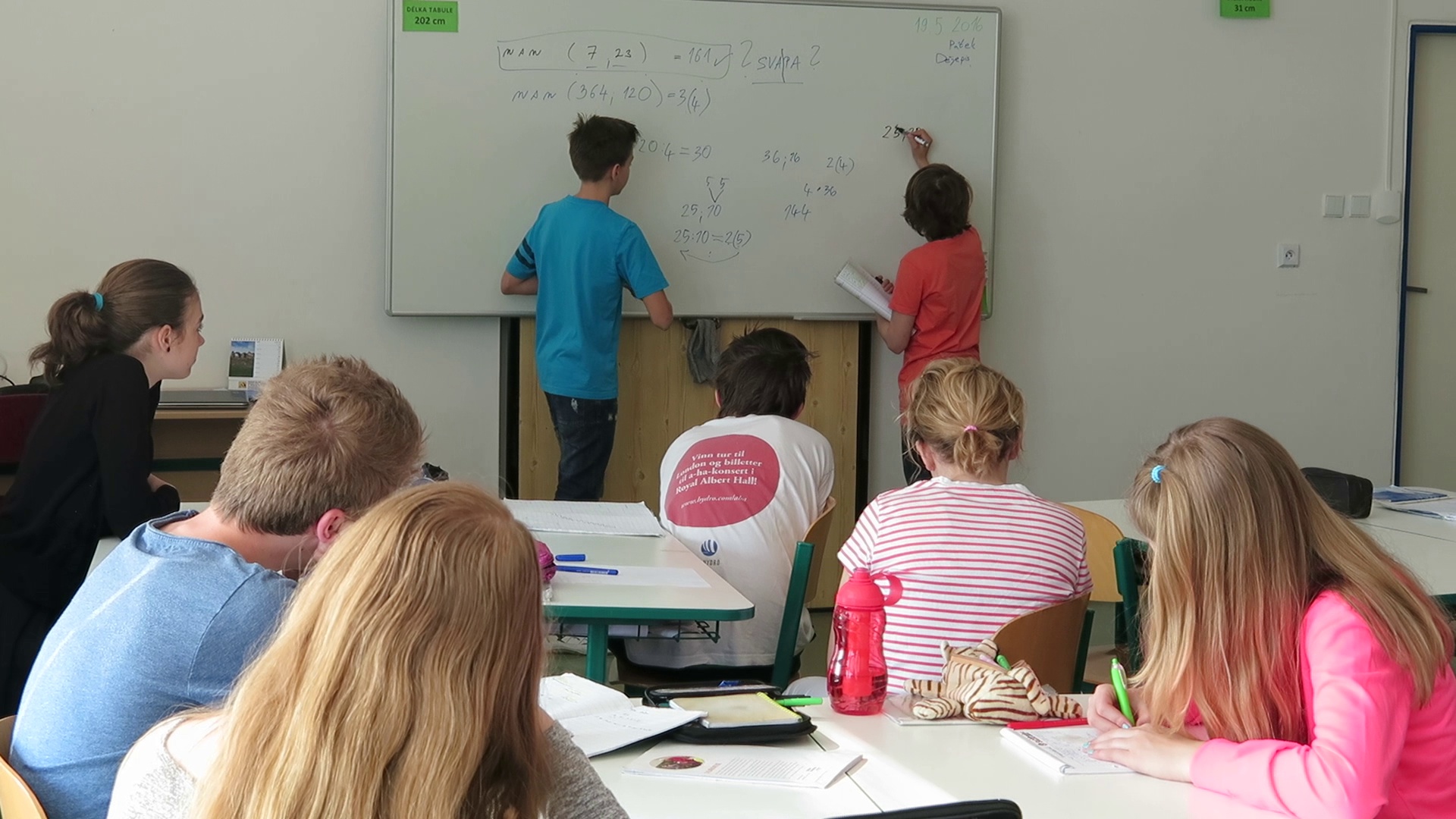

What is taught is not presented, “served” by the teacher. Children’s own effort and hands-on experience leads to knowledge that is more permanent.

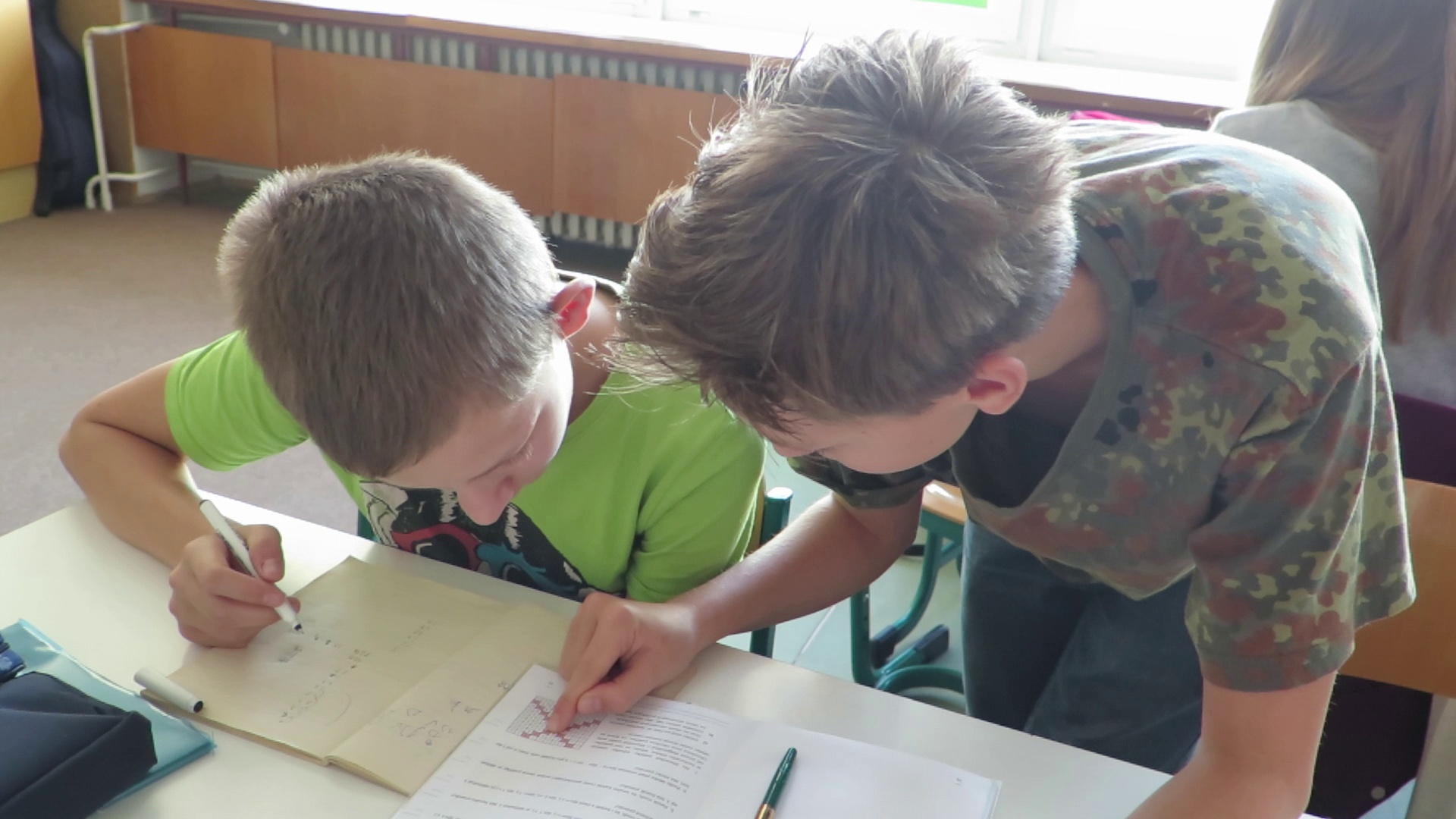

Children are encouraged to cooperate with their classmates as well as to formulate and verify their own conjectures. Most of the work has the form of discussion, reasoning and justification. I perceive this as very important. What is taught is not presented, “served” by the teacher. Children’s own effort and hands-on experience leads to knowledge that is more permanent. This way of teaching guides children to respect each other, they do not ridicule each other. They regard a mistake as a natural part of the learning process – they communicate their solution to the others and thanks to open communication they reach a conclusion together.

“If a person tries to understand, they always will.”

And how is mathematics taught by the Hejný method perceived by Viky, the girl who plays a key role in the story above? “If a person tries to understand, they always will. They are everyday situations that we calculate. It is enough not to panic and not to take everything as difficult as it may appear at first sight. That leads to failure. My motto is “everyone has mathematics in them, we just need different amount of time to understand”. That is why when I see someone lost in math or if they ask me for help I am very happy to help. There is nothing nicer than when they start grasping the connections or relationships and then they try to show to others and to the teacher in lessons that they finally understand what the source of difficulty was for them. In addition, if they are my friends, I share their pleasure from and enthusiasm about their success with them.”

I have never doubted that there is a lot of so-called added value to teaching mathematics using the Hejný method. The above-described manifestation of true, selfless friendship, humanity among teenagers only supports my opinion.

Disinterest, reluctance to learn new things, boredom? This is something we never come across in lessons of Hejný’s mathematics. And with pleasure and appreciation I must add that creative thinking the children develop goes far beyond the subject mathematics.

The excerpt comes from the magazine Školní poradenství v praxi č. 3/2017, Wolters Kluwer. The whole article, Školní poradenství v praxi: Can children start with the Hejný method as late as lower secondary school level?, is available here in PDF.

Mgr. Jitka Linhartová,

A teacher at elementary school ZŠ Dr. J. Malíka in Chrudim

Comments